On April 23, 2024 from 6 to 7:30PM, C3EN cohosted a virtual violence prevention town hall with Phalanx Family Services featuring a keynote by Pilot Awardee Chuka Emezue, PhD, MPH, MPH, CHES, assistant professor in the Department of Women, Children, and Family Nursing at Rush University College of Nursing. About 40 people attended the meeting, including researchers, community leaders, and community members.

Emezue began his presentation, “Trauma- and Equity-Focused Support for Men and Boys on Both Sides of the Gun,” by declaring a “call to action” to address pediatric and youth violence, which he defined as “acts of physical, emotional, or psychological harm, aggression, or abuse involving children and adolescents,” including bullying, child abuse, domestic/dating violence, gang-related violence, gun violence, school violence, and violence among peers.

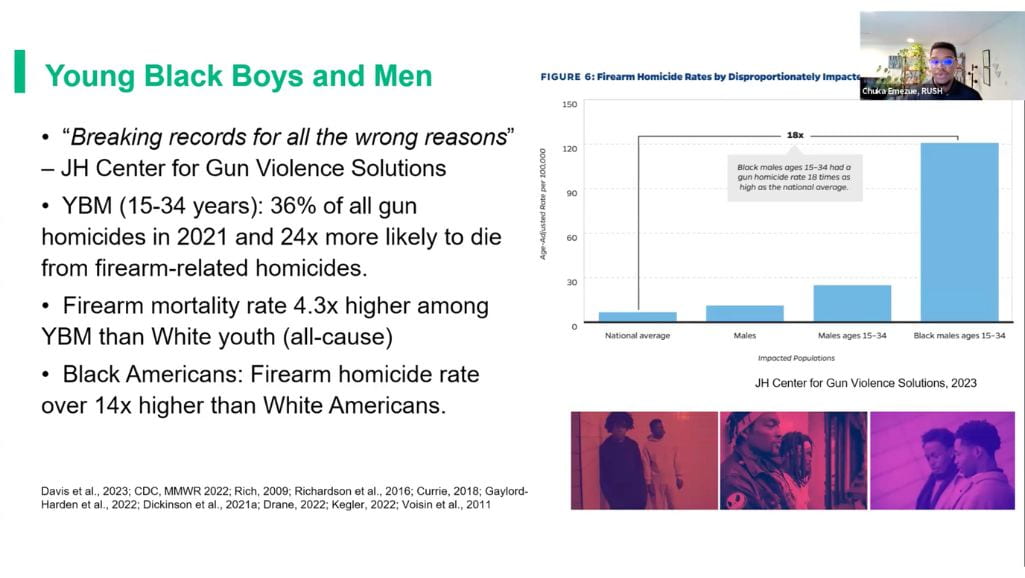

Emezue noted an uptick in violence since 2019, primarily gun-related and gender-specific. “Males are leading the charge. Since 2018 there has been a steady rise in firearm deaths of children and adolescents. Firearm homicide is the third leading cause of death for all youth aged 10 to 24,” he said, pointing out that US teens aged 15 to 19 are 17 to 82 times more likely to die of firearm-related homicide than their peers in other countries.

The problem is exceptionally pronounced among Black youths, especially boys. “Young Black boys have a six times higher firearm death rate than any other racial group in the country,” said Emezue. “They’re breaking records for all the wrong reasons.”

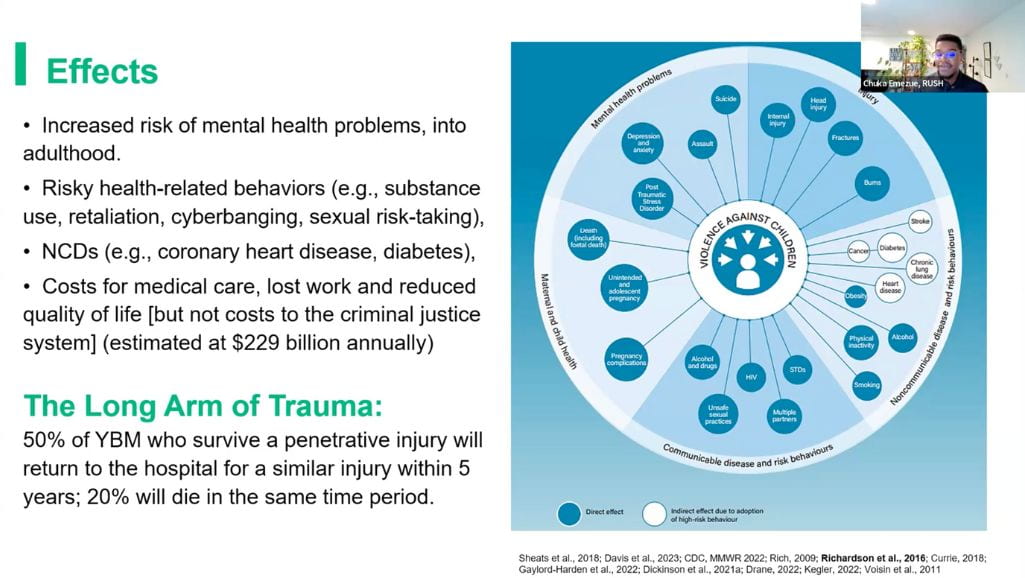

The consequences of gun violence can have far-reaching effects beyond physical injury, including mental health issues such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicide, and exacerbate risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease due to elevated cortisol levels in response to stress. “One in two young black boys who survive a penetrative injury will return to the hospital for a similar injury within 5 years … and about 20% of that group will not survive for five years,” he said.

To address gun violence, we must address suicidality, intergenerational trauma, structural racism and racial trauma, and overcoming the stigma of getting treatment, particularly for young men. Black Americans are the least likely population to utilize mental health services. Because only 2% of psychiatrists and 4% of psychologists are Black, the shortage of providers with shared lived experience is a significant problem (“Some of these numbers are so small they might as well fall within the margin of error,” he said).

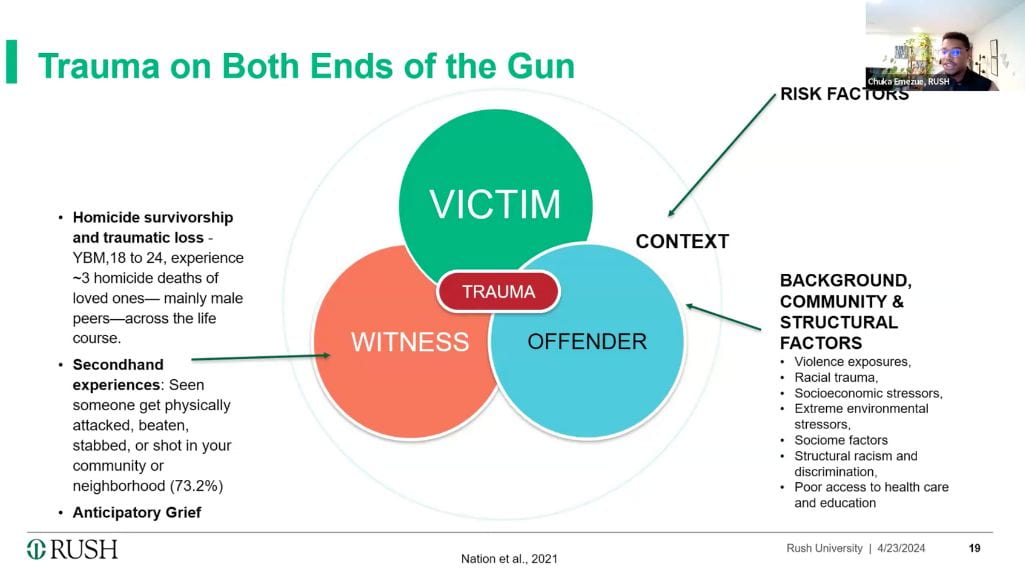

“It’s hard to hear a young man say he can count more friends that died than fingers on his hands. It’s hard to hear a young man say he doesn’t think he might live past 24,” said Emezue. “We often have to approach this conversation thinking about the multiple identities that these young boys occupy as victim, offender, and witness to violence”: interviews with young Black male Chicagoans demonstrate that most had witnessed violence, many had perpetrated violence, and about 20% had carried a weapon 2 or 3 times in the past month. Violence had a substantial overlap with substance abuse: about 20% of urban youths seeking emergency care related to violence used a substance in the hours immediately preceding.

Programs addressing violence are not scarce (“anywhere you look in Chicago, there’s a program”); however, young Black males rarely use these services. Instead, many rely on risky coping strategies such as pornography, substance use, and cyberbullying.

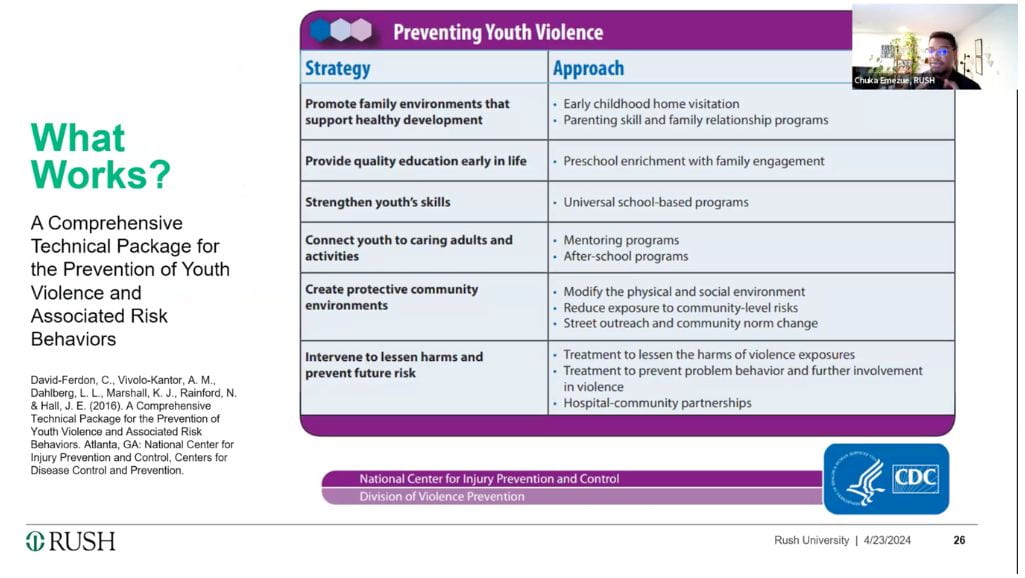

Many successful programs use violence prevention strategies released by the CDC in 2016, which encourage early child interventions, promoting family stability, quality early education, mentoring and after school programs that build skills, and creating protective community environments.

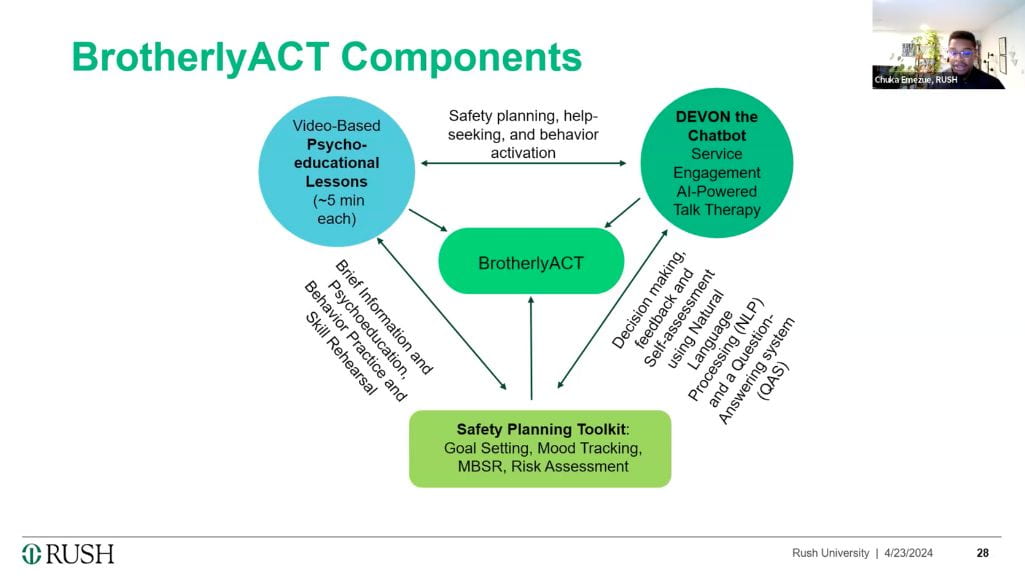

Emezue’s program, the BrotherlyACT Project, includes a digital app based on acceptance and commitment therapy designed by and for young Black men. The app provides short videos modeling topics such as gang resistance, drug refusal, coping strategies, and conflict resolution, tools to monitor moods and set goals, an AI chatbot to provide talk therapy, and referrals to in-person resources by zip code. Nevertheless, “technology is not the end all be all,” he said. “It’s just augmenting what we already have, not replacing what we’re doing right now in the community.” An in-person component includes inviting youth to serve on an advisory board and attend boot camps focused on leadership and entrepreneurship.

In the discussion that followed, Dori Collins, president of District Outreach Initiatives, which educates parents on leadership and community engagement, suggested that communicating resources to parents could encourage more youth participation in existing programs. She also noted the need for nuance in addressing types of violence, since girls were more likely to experience suicidal ideation and self-harm. Robert M. Douglas, Sr., remarked that community organizations often don’t have the data needed to obtain federal funding for gun violence research, which causes funding to go to policing and other “hard” interventions.

Doriane Miller, co-director of C3EN’s Community Engagement Core, noted that cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on changing thought patterns in the present, could be more useful as an intervention than psychodynamic therapy, which focuses on the past. Emezue concurred, saying, “I’ve seen young men go to prison because they felt ‘disrespected’ … we need to tell these young people that the fact that you think it doesn’t mean you are it – your thoughts and your behavior are two separate things… CBT can help separate thinking from behavior.”

Others suggested that programs addressing youth violence need to focus on the whole family, build community, and provide spaces where youths can feel safe, seen, and respected.